July 2018

How can people behind bars access poetry classes? How can they share their visual art with the outside world? What organization aspires to help inmates reimagine who they are and who they could be?

The Freehand Arts Project, founded by Kelsey Shipman, provides an artistic outlet to those imprisoned in the county jail system. As I step into Kelsey’s home, two dogs are just as welcoming as their owner. Something is compelling and engages my curiosity everywhere my eyes turn. The art on her walls varies from unique illustrations to bold paintings. Her home is a blanket of shadows filled with warm light and colorful walls. I am fascinated to learn more about her and what led her on this path.

As a writer/poet with an MFA from Texas State University, Kelsey has always been intrigued by the incarceration system. “There is a trend of poets, particularly those interested in social justice and activism, who have worked in and outside jails.” She names writers and poets such as Asha Bandele, Jimmy Santiago Baca, and local Austin poet Raúl Salinas, whom she especially admires. She yearned to experience and share the power immersive writing could have within this demographic firsthand.

After moving to Austin in 2009, she relentlessly sought out different organizations designed to help inmates through a creative channel. Four years later, while teaching at a university during her graduate program, another teacher mentioned her regret of relinquishing a teaching position at a jail since she was moving away and asked Kelsey if she would be interested in taking over. Kelsey was happily surprised and elated that the opportunity to work with inmates had finally arrived and enthusiastically accepted. But by the time she began, the organization had disbanded, and suddenly, she was the only teacher within the system, with no financial support or fellow teachers to lean on. This did not deter her drive. She simply pressed on.

She voluntarily worked in the jails teaching poetry once a week to minimum and maximum security men and women for a year. After a year, inmates frequently approached her with various requests, asking for classes in the afternoon, classes about fiction, and classes for visual arts. At that moment, she decided to get in touch with befriended writers and find out if they may be interested in participating in this experience. After assembling a small, capable, enthusiastic group, her vision became clear, and she decided to launch a new nonprofit. Freehand Arts Project was born and began forming respectful ecosystems for inmates to thrive and feel safe to express their stories.

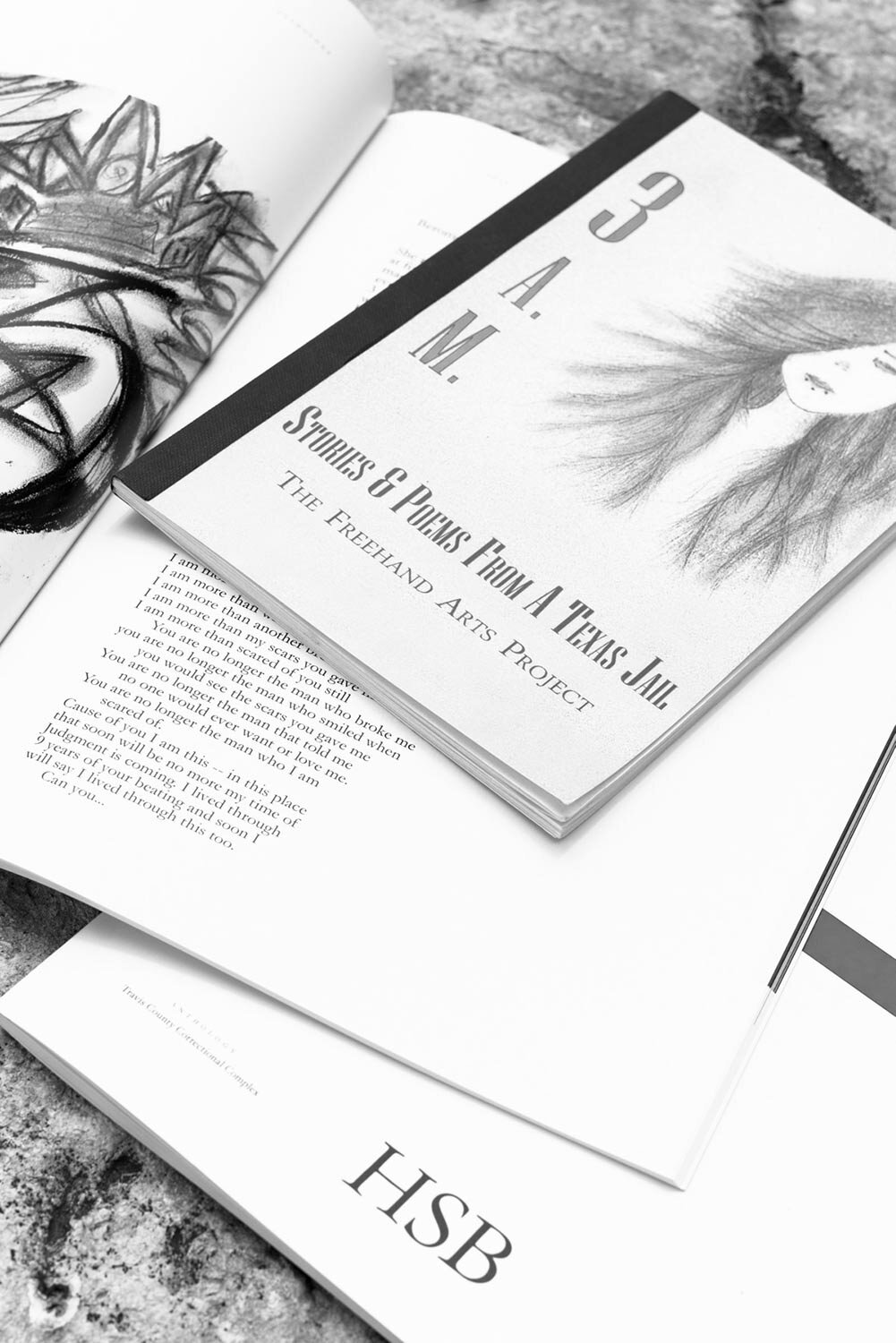

Freehand currently offers creative writing, poetry, visual arts, and hopefully soon, memoir/nonfiction writing classes. They also offer artist workshops and a chance for inmates to contribute work in Freehand’s published anthologies, which are released and available to the public. The fourth anthology, released this year, has made Kelsey particularly proud. “Now the broader public can read their work. It helps humanize our students and it gives people a look into what being in jail is really like.” As I read my copy of the anthology, I felt moved and haunted by the poems and imagery. These writers’ and artists’ vulnerability is undeniably raw and resonant, impressively accessed and conveyed while inhabiting a constricted environment. “The punchline is where this is being written again and again. When you’re free to move around, the punchline isn’t the dramatic irony of where you are all of the time, “says Murphy Anne Carter, current executive director of Freehand.

One of the hardest decisions Kelsey had to make was letting go of the reins and stepping down as executive director. Her busy teaching schedule in public and private schools gradually took its toll. She knew she needed to pass on most responsibility to someone else for Freehand to grow. Luckily she found the right personality, passion, and consistent vision within Murphy. Training under Kelsey, Murphy gained confidence and Kelsey’s trust to spearhead and steer the ship, which allowed the engines to become bolstered by new energy and ideas.

Murphy, a former high school English teacher in NYC’s Hell’s Kitchen and current grad student, is just as passionate and even more exuberant about Freehand’s direction. Since August 2016, her leadership has resulted in a WeWork creator grant award with the help of fellow teacher Liz Moskowitz, successful artist workshops attended by well-renowned authors such as Eileen Myles, a well-attended gallery opening, and more published anthologies. But her most enormous love of all is teaching. “This is the big twist,” she says with a smile, “I was teaching at a school where everyone didn’t want to be there, and it felt like a jail, and now I teach at a jail, and everybody wants to be in my class and loves it.” Stepping into the leadership role, Murphy knew many artists and writers with the skills and desire to be a part of this mission. So she eagerly presented this fantastic teaching opportunity to many new artists and authors, hoping they would love it as much as she did.

The effect these teachers have had has been irrefutable. You can read and sense it in the students’ writing and art pieces. “Multiple students have said this is the only time they don’t feel like they’re in jail,” Murphy says. “What I hate most is that jails are treated as ‘of course you want to forget it as soon as you leave, absolutely.’ But it’s not like good things don’t happen there. The students end up knowing that there is an opportunity for anything to be transformative, something as state-sanctioned and selective as a jail.”

Kelsey knew how transformative writing could be for people with complex life stories and wanted to pass on this alleviating process, particularly to women. “Writing for me is an avenue for healing, “says Kelsey. “It helped me transcend and heal from many difficult family experiences I had growing up. So teaching in the jail, it’s like that turned up to eleven. So many people in jail have terrible life stories. So many people in jail come from poverty, and a side effect of poverty is all of these things: domestic abuse, people going in and out of jail, parents around and not around, being raised by other relatives, sometimes food scarcity, people dropping out of school…They all have these stories they want to tell but nobody wants to listen.”

The county jail consists of various people waiting to attend court for what they have been accused of. It is a holding space for people who cannot afford to place bail and includes a wide range of crimes. Some will be found guilty and some will be found innocent. Some go in and out multiple times and some are experiencing it for the very first time. Some are very young and some are old. But sadly, much of society doesn’t care what social circumstances brought them to this place. They are now associated with the term “inmate.”

“If you are an inmate, then people take that title and think that you’re a criminal, you deserve to be there, you don’t deserve to have any attention. I mean, the stuff people say about inmates in the media is crazy, “Kelsey says exasperatingly. “My students have so much to express and we try to create an avenue for them to talk about their feelings. But the really powerful part about art is that you actually transform your feelings. So you can change a lot of the pain and anger into a poem and suddenly, it’s a beautiful piece of art.”

Kelsey and Murphy want to continue this vulnerable and safe environment outside the jail walls and create a physical space between downtown and county jail. Building this similar presence will give former inmates a familiar and uplifting space to go to when they are released. It will also remind them that their positive artistic connection with the outside world through their work in the anthologies doesn’t have to stop. Kelsey hopes they have new affirmations and realizations such as, “I can be an educated person, I can be an artist, I could be a functioning member of society without having to resort to these desperate measures.” But she also understands that it is easier said than done.

“I’ve had a student say to me, ‘I don’t know what to do. The only way I know how to make money is this. And if I work part-time at Pizza Hut, I’m never going to make enough.’ And I don’t know what to say to that,” she says sadly. “I’ve seen this repeatedly. If they don’t have an education, if they don’t have job skills, don’t have a supportive family, don’t have any money, they go back to the life they knew.” Kelsey believes this physical space might help combat recidivism by serving as a transition post for inmates and become an ancillary service when they get out. They imagine it as a place where former inmates can come and participate in writing workshops with special guests, sell anthologies, and hang inmates’ artwork for sale. The ultimate dream would include a social service component, allowing people to access a social worker if needed. They are also planning to expand their program to jails in New Orleans.

“So many of our students, when they’re in jail, they are in this isolated environment. They come to our classes and I feel like they reach some of their original values, hopes, dreams, and morals. They tell us they want to go to college and study poetry, but when they get out…” Kelsey pauses. Clearly, a consistent presence outside the jail that reintegrates and welcomes former inmates is a heartfelt necessity for the students she cares about.

The idea of being vulnerable and free to express yourself is challenging in the real world, no matter how painful your story is. So designating a space and time for that kind of liberation, especially behind bars, is a beautiful and humane endeavor. The teachers of Freehand transform a place blanketed in dark shadows into a warm, welcoming class environment full of colorful personalities. They enable people who’ve made mistakes to discover and hone their innate talents and connect with their own self-worth, which many have forgotten to do along the way.

So worthy that the name of Kelsey’s nonprofit actually came from an inmate. Kelsey loved it as soon as she heard it because it expressed what she hoped Freehand Arts Project would accomplish. “I loved the double meaning of freehand, being free both outside of jail but also inside yourself to be who you are.” Internal freedom can never be taken away, and because of this special nonprofit, their students in imprisoned circumstances feel and remember that.

2022 UPDATE:

Today, Freehand Arts Project is still operational as much as possible. Like many other nonprofits that provide services in a group setting, the pandemic forced changes on their entire program. “We were grasping for straws as an organization for how to reach people on the inside with the lack of transparency, communication, and accessibility that occurred after March 2020,” says executive director Murphy Ann Carter. They created freely distributed workbooks to engage their students outside class to overcome this obstacle. These journal-type packets offer different prompts that help students navigate and think about what they would like to express independently. Recently, the teachers of Freehand were also given access to virtual teaching, a generally difficult task for all teachers, let alone for teachers teaching incarcerated people who crave authentic connection. Even though the challenge of the pandemic is honorably being met by Murphy and the rest of her team, it still highlights and exacerbates the inequities of the incarcerated daily. “I can’t even begin to describe how much this pandemic has shown again and again that this system of putting people in cages shouldn’t exist,” observes Murphy.

When she is not working on Freehand, the executive director works at Texas After Violence Project, a community-based oral history archive dedicated to documenting and preserving stories around mass incarceration, police brutality, and the death penalty. And Kelsey Shipman, the founder of Freehand Arts Project, is now a happy new mom who recently returned to the United States after teaching in Asia for two years.